It seems like only yesterday that the 20-year-old left-hander from Etchohuaquila, Mexico, was baffling hitters with his screwball, looking skyward as he wheeled toward the plate.

As a young sportswriter in South Florida with The Stuart News in May 1981, I got to sit in on a national telephone conference call that included Valenzuela; his interpreter, longtime Spanish broadcaster Jaime Jarrin; Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda; and several members of the team.

Valenzuela had begun the 1981 season with a 7-0 record and a ridiculously low 0.29 ERA.

“To be honest with you I didn’t think I’d get that far,” Valenzuela said at the time through his interpreter. “Before the season it never came to mind.”

“You can’t do that with mirrors or with luck,” Lasorda added. “Amazingly, nothing seems to rattle him. The guy makes the right pitch at the right time.”

It was an exciting time. Valenzuela would post a 13-7 record during the strike-marred split season of 1981 and pitched to a 2.48 ERA. He would win the National League Cy Young Award and was the third consecutive Dodger to win Rookie of the Year honors (pitchers Rick Sutcliffe and Steve Howe preceded him and infielder Steve Sax would win in 1982).

Valenzuela spawned what would be known as “Fernandomania,” a baseball and cultural phenomenon. “El Toro” pitched in the majors for 17 seasons — 11 in Los Angeles — and earned 141 of his career 173 victories while wearing Dodger blue.

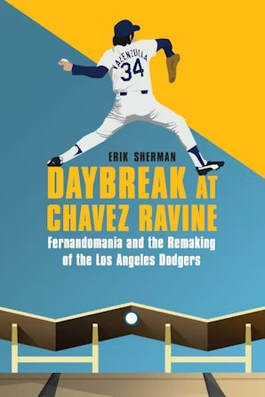

That is what author Erik Sherman captures so well in his latest book, Daybreak at Chavez Ravine: Fernandomania and the Remaking of the Los Angeles Dodgers (University of Nebraska Press; $32.95; hardback; 249 pages)

Erik Sherman.

Erik Sherman.

The team performed well on the field and won National League pennants in 1963, 1965, 1966, 1974, 1977 and 1978, but the franchise had never found a way to soothe the bitterness of the Mexican American community. Latinos in the Los Angeles area had never forgiven the city of Los Angeles and Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley for cutting a deal to build a stadium at Chavez Ravine, which displaced hundreds of families during the late 1950s.

During the early 1950s, the city evicted approximately 300 families so a low-income, publicly funded housing project could be built. However, Los Angeles sold the land to O’Malley and the evicted residents — who had been promised the first pick for apartments in the proposed Chavez Ravine housing projects — were left holding the bag and were not reimbursed.

It came down to a contentious referendum, called Proposition B, to build the stadium, and O’Malley — who had pulled up stakes in Brooklyn to move west — won by 24,293 votes out of a total of 666,577.

O’Malley built Dodger Stadium, a magnificent complex that opened on April 10, 1962, but Mexican American fans stayed away in droves. It did not help that in May 1959, television cameras recorded deputies carrying residents from their frame houses in Chavez Ravine as bulldozers knocked down the structures, according to Andy McCue’s 2014 book, Mover & Shaker.

Bad for public relations, although city officials blamed the media for turning the eviction into “a cartoon morality play,” McCue would write.

Despite the Dodgers winning six pennants and two World Series at Dodger Stadium, Mexican American fans were hard to find. Even the three pennants during the 1970s did not help.

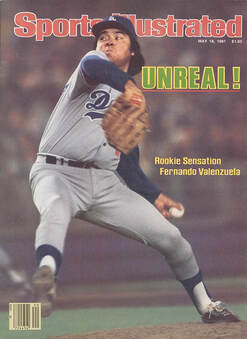

Fernando Valenzuela made the cover of Sports Illustrated during his hot start in May 1981.

Fernando Valenzuela made the cover of Sports Illustrated during his hot start in May 1981.

Valenzuela’s impact on the Latinos “was more impactful and profound than any no-hitter or World Series he ever pitched,” Sherman writes.

Longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully would observe that Fernandomania looked like “an almost religious experience.” Sportswriter Lyle Spencer told Sherman that “Fernandomania was a full-on festival every time he pitched.”

Pressed into action in 1981 when Jerry Reuss was scratched due to calf injury, Valenzuela became the first Dodgers rookie to start on Opening Day. It was also his first major-league start and he pitched a five-hit shutout.

Sherman guides the reader through Valenzuela’s blazing impact, when he first 12 starts at Dodger Stadium were sellouts. He is familiar with writing about baseball and digging nuggets out of his extensive research, which is also on display in Daybreak at Chavez Ravine.

Sherman has written books about the 1986 Mets (Kings of Queens), the 1986 Boston Red Sox (Two Sides of Glory) and co-authored autobiographies with Davey Johnson, Glenn Burke, Steve Blass and Mookie Wilson.

Sherman’s 2019 book, After the Miracle, with Art Shamsky, was a warm and poignant look at the 1969 New York Mets.

Valenzuela declined to participate in Sherman’s latest project, but that enabled the author, podcaster and 2023 inductee into the New York State Baseball Hall of Fame to interview former teammates and opponents. Those interviews provided a fuller, more analytical look at Valenzuela.

Sherman pulls out rich, insightful observations from a diverse group of players, including Valenzuela’s teammates — Dusty Baker, Rick Monday, Jerry Reuss and Steve Garvey, to name a few. Dodgers scout Mike Brito, Jarrin and even opponents like pitchers Bill Lee and Jeff Reardon also offer valuable perspective.

“He captured everyone’s attention,” Monday told Sherman. “Not right away, but when he did, he owned it.”

Valenzuela’s success in 1981 caught all of baseball flat-footed.

“I wasn’t thinking he was going to be the ace of the staff — that’s for sure,” former Dodgers executive Fred Claire told Sherman.

Sherman writes about Valenzuela’s lunch with President Ronald Reagan and Mexico’s president, José López Portillo, a monumental day for a 20-year-old rookie who still took it all in stride. Valenzuela’s career was much more successful than that of Portillo, who was Mexico’s leader from 1976 to 1982. The New York Times reported in Portillo’s 2004 obituary that he brought Mexico to “the brink of economic collapse” and “was considered one of the most incompetent leaders of Mexico's modern era and his government among the most corrupt.”

Fernandomania, on the other hand, did not seem to have any limits, Sherman writes. Remember, he starred in the era before social media and modern marketing savvy, but it was not unusual to see homemade images of Valenzuela on T-shirts, posters and murals. Valenzuela was selective in what products to advertise but became wealthy.

The baseball strike certainly prevented Valenzuela from winning 20 games in 1981, but the eight-week stoppage, which forced the cancellation of 713 games, also afforded him a chance to rest and recharge. After an 8-0 start, Valenzuela was 9-4 but still led the league in complete games, innings pitched shutouts and strikeouts. The man needed a break.

The Dodgers got one too, as it was determined that teams leading their divisions when the strike began would be declared first-half champions and would earn a spot in the playoffs regardless of how they performed. It was a quirk that prevented the Cincinnati Reds, who had the league’s best record but finished second in both halves — from competing in the postseason.

When baseball returned, Valenzuela was the starting pitcher for the N.L. in the All-Star Game. He would be named to the All-Star team six times during his career.

As for the Dodgers, the 1981 playoffs would be a study in determination. Down 0-2 to Houston in the divisional series, Los Angeles would win the next three games at Dodger Stadium to advance. That included a Game 4 complete-game victory pitched by Valenzuela, as the left-hander had a 1.06 ERA against the Astros.

Against the Montreal Expos in the NLCS, the Dodgers prevailed in five games when Valenzuela pitched a gritty 2-1 victory that was helped by Monday’s clutch home run that snapped a 1-1 tie with two outs in the top of the ninth inning.

The Expos were managed in the playoffs by Jim Fanning, who took over for Dick Williams. Sherman described Williams as having a “vinegary personality.”

That’s an understatement.

During spring training in 1981 I approached Williams at Municipal Stadium in West Palm Beach because I was writing a story about Gary Carter, specifically about his baseball card collection. I introduced myself and started to ask if he had a minute to talk about Carter. He looked at me and asked, “Who are you with again?”

When I told him, he shook his head, turned on his heel and walked away, saying, “Nahhh.”

I must have looked shocked, since New York Yankees manager Gene Michael was standing nearby, laughing.

“Don’t worry, kid, he’s always like that,” Michael chuckled.

Well, that was a nice consolation. He certainly lived up to his name.

Reuss told Sherman that the effort was impressive because he did not have his best stuff.

“I imagine every time Van Gogh picked up a paintbrush, he didn’t create a masterpiece,” Reuss said.

Valenzuela had plenty of them in 1981, and the Dodgers would win their first World Series title since 1965.

The losing pitcher in Game 3, George Frazier, who died on June 19 at the age of 68, became an unfortunate answer to a trivia question. He would become the first pitcher to legitimately lose three games in the World Series, as he was also saddled with losses in Games 4 and 6.

Claude Williams, who pitched for the Chicago White Sox in the 1919 World Series, also lost three games, but the team was later found to have thrown the postseason series, according to the Society for American Baseball Research. Williams was not one of the eight “Black Sox” players implicated in the scandal, by the way.

Of course, Valenzuela’s career did not begin and end with the 1981 season. There were other seasons, other accolades and other feats — 21 wins in 1986, a no-hitter in 1990, and 13 wins in 1996 as he helped the surprising San Diego Padres win the N.L. West.

But the 1981 season was magical.

The only glitch I saw in Sherman’s work was his statement that Hideo Nomo was the first Japanese-born player to reach the majors. That honor actually went to another pitcher, Masanori Murakami, who made his debut with the San Francisco Giants in 1964, according to MLB and documented by Robert K. Fitts in his wonderful 2015 biography, Mashi.

Sherman ends his work by wondering why Valenzuela’s No. 34 had not been retired, although no one has worn it since he has left the Dodgers. That oversight will be corrected in August, when his uniform will be retired during ceremonies and events during a three-game stretch.

Sherman’s research, coupled with his interviewing skills, makes for a compelling narrative.

Valenzuela “was like a composite of the Beatles — only in Dodger blue,” Sherman writes in his preface. “His appeal was universal. “He wasn’t just a baseball player, he was a healer in a time when, much like today, many Americans viewed Mexicans as second-class citizens.

“He was to Latinos what Jackie Robinson was to Black Americans. And their feelings for Valenzuela have only grown stronger over the years.”

“He’s for real,” teammate Davey Lopes said during that 1981 conference call.

He still is, and remains a revered figure in Dodgers history. Sherman does a wonderful job of piercing through Valenzuela’s quiet shell to paint a complete picture of a beloved figure.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed