Certainly, there are others. Outfielder Lyman Bostock was murdered in 1978 and pitcher Jose Fernandez was legally drunk and had cocaine in his system when the boat he was piloting crashed off the coast of Miami Beach in September 2016. Drug use drastically altered the Hall of Fame projections of Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry.

Those are just a few. But Reiser was young, talented, aggressive and appeared to be a lock for the Hall of Fame.

If only the walls had been padded back then ...

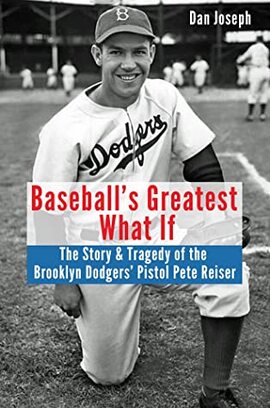

Author Dan Joseph explores Reiser’s career in Baseball’s Greatest What If: The Story & Tragedy of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ Pistol Pete Reiser (Sunbury Press; $19.95; paperback; 282 pages), telling a story that needed to be told.

“Pete Reiser had everything but luck,” his first major league manager, Leo Durocher wrote in his 1975 autobiography, Nice Guys Finish Last.

Reiser, Durocher said, “just might have been the best player I ever saw.”

So, what happened? The answer is obvious, but Joseph takes the reader deeper, delving into newspaper articles from the 1940s and utilizing a solid bibliography. Joseph’s chapter notes are extensive and reveal the depth of his research.

It is the same approach Joseph used in his second book (and first sports book), 2019’s Last Ride of the Iron Horse: How Lou Gehrig Fought ALS to Play One Final Championship Season. Most baseball fans know about Gehrig, baseball’s original Iron Horse. The story that most hear is that Gehrig came to camp in 1939 and struggled mightily, with his power sapped and his reflexes shot from the disease that would eventually kill him two years later. Joseph shows in great detail how 1938 should have been a red flag for the Yankees — and Gehrig himself, as he was mired in a slump for much of the season.

It took a late-season surge to bring Gehrig’s numbers up — as late as June 19, his 35th birthday, he was only batting .267 — but he finished the year with a .295 average, 29 homers and 114 RBI. Those were great numbers for most, but a huge step down for the Yankees’ first baseman.

Reiser hit the wall with a “sickening thud,” and at best, he suffered a concussion.

Joseph lists the contemporary news reports of the incident, which were extensive, and then poses the question — how badly was Reiser hurt that day?

“The skull fracture became part of the Pete Reiser legend,” Joseph writes, mentioned by the player in interviews and by sportswriters in their articles and columns. “The problem with these accounts is that outside Pete’s recollection, there’s no evidence his skull was actually cracked on the fateful play.”

The medical records are long lost, and the people involved have been dead for years, so the reader has only the reported information to trust.

And trust did not always translate into accuracy. Put a drink in Reiser’s hands late in his life, and the stories began to flow. Sometimes, they matched the true narrative.

“Reiser was not above exaggerating his feats and downfalls or simply misremembering events,” Joseph writes.

For example, Joseph quotes an Aug. 7, 1942, article in the Daily Record of Long Branch, New Jersey, explaining how Reiser met his wife. Reiser had declined an invitation to a party because “I didn’t have a girlfriend to bring with me.” The friend assured him that his girlfriend had a friend she wanted him to meet. That was Patricia Thornton Hurst, who would marry Reiser.

Great story. The account was slightly different several months earlier in a Feb. 12, 1942, note in the St. Louis Star and Times. In Reiser’s hometown newspaper, “It seems that a toothache led to ‘heartache.’”

The story noted that Reiser visited a dentist in the Missouri Theater Building. The dentist, a friend of Reiser’s, introduced him to his future wife, “who was an attendant in the office.”

Love at first overbite? Both stories are compelling, although I prefer the dentist story.

The couple was married in Brevard County, Florida, on March 29, 1942, according to online marriage records.

Reiser could have been one of baseball’s greatest players. He finished second in the National League’s MVP race in 1941 after leading the league in hitting (.343), triples (17), doubles (39), runs (117) and total bases (299). These numbers take on added wonder after realizing that eight days into the season, Reiser was hit in the right cheekbone by an Ike Pearson fastball. Still, he led the Dodgers to the 1941 pennant, Brooklyn’s first in 21 years.

Brooklyn won 104 games in 1942, ending the season with an eight-game winning streak, but finished two games behind the St. Louis Cardinals, who won 106. Four years later, the two teams met in a best-of-three playoff series and the Cardinals won both games.

During that 1942 season, Reiser batted .310 and led the league in stolen bases with 20. He would electrify baseball fans by stealing home seven times in 1946.

“If the Dodgers didn’t have Reiser, they would pay $150,000 for a center fielder like him,” NEA Service sports editor Harry Grayson wrote in June 1942.

Reiser’s eligibility for military service during World War II was the subject of spirited debate before he went into the Army.

Sportswriters caught up in patriotic fervor were not always kind.

William J. Madden wrote in a May 1942 column that Frank T. Kelliher, chairman of a draft board in Brooklyn, “won the National League pennant” for the Dodgers when he granted Reiser’s appeal after he was classified as 1A.

“It seems (Reiser) supported practically everyone on Flatbush Avenue, including a wife, his parents, four sisters, and a brother,” Madden wrote. “He also gave his old suits to a few cousins.”

For all of that hyperbole, Reiser still missed three full seasons due to military service. He did not see duty overseas but did play at Fort Riley for the Army. “Prairie locked,” Joseph writes.

Reiser wanted to play, even with injuries, and Durocher was more than happy to oblige. His kind of player.

“Nobody makes more a difference than Reiser — even a one-armed Reiser,” Joseph quotes the Lip from a 1946 article that referenced Pistol Pete’s injured right arm.

How dangerous was Reiser at the plate? Bill Bevens was on the verge of throwing a no-hitter in Game 4 of the 1947 World Series. Reiser was sent up as a pinch-hitter with two outs in the bottom of the ninth inning. Batting despite suffering from a broken ankle, Reiser worked a 3-1 count when Al Gionfriddo stole second. That led Yankees manager Bucky Harris to go against baseball wisdom and walk Reiser — putting the winning run on base.

Eddie Miksis ran for Reiser, and Cookie Lavagetto smashed a two-run double off the right-field wall to end the no-hitter and win the game for the Dodgers. Harris was second-guessed for walking Reiser, but said he feared that Bevens would try too hard to throw a strike and that Reiser would connect solidly.

Injuries plagued Reiser throughout his career. During World War II — he lost three full seasons to military service — Reiser played baseball for the Army and in August 1945 chased a fly ball over a makeshift fence, falling into a 10-foot ditch and separating his right shoulder.

Reiser crashed into the left-field wall at Ebbets Field in 1946 while trying to catch a drive from the Cardinals’ Whitey Kurowski. And in 1947, Reiser was given the last rites in the clubhouse after hitting his head against the Ebbets Field’s center field wall while trying to corral a drive from Pittsburgh’s Culley Rikard.

Joseph provides a handy graphic that shows the seven major collision Reiser had with concrete walls.

Reiser also cut his back running into an Ebbets Field exit gate.

It is a shame the designated hitter was not an option in the 1940s. That’s not a knock on Reiser’s outfield skills, but his aggressiveness and fearless pursuit of fly balls were detrimental to his career — and, to his health. Reiser wanted to catch everything in sight, even if it meant banging his head against the wall.

Joseph adds a chapter called “The Other Great What-Ifs,” providing short vignettes about players who had potential to become stars but either died or suffered career-ending injuries. Some of the players include Cecil Travis, Mark “The Bird” Fidrych, Josh Hamilton, Herb Score, Ken Hubbs and J.R. Richard.

It’s an intriguing narrative, but it is the ninth chapter in a 12-chapter work. It stops the flow of the Reiser storyline and probably would have served the reader better as an appendix, or perhaps between Chapter 11 (“Baseball Afterlife”) and Chapter 12 (“Legacy”). The information is great but seems to be awkwardly placed in the book. Just a thought.

To “run through a brick wall” is an old idiom that means a person will do whatever it takes to succeed. A photograph of Reiser should be posted next to that definition. He was an exciting, breathtaking player who played with abandon and in just one gear — all out.

Joseph gives the reader insights into the thinking of Dodgers GM Branch Rickey and his contract battles with Reiser, and adds the color of 1940s reporting from New York baseball writers.

“Reiser was considered a potential superstar but ruined his career when he ran into outfield walls several times, suffering serious head injuries,” The Associated Press wrote in its obituary for Reiser on Oct. 27, 1981, two days after his death.

That was Reiser’s career in a nutshell. But there was so much more, and Joseph paints a fuller, richer portrait of the Dodgers’ enigmatic star. With a little luck, Reiser could have played in four World Series in Brooklyn during the 1940s. He made it twice, but he certainly would have been a fixture for the “Boys of Summer” had he stayed injury-free into the 1950s.

But that’s another “what if.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed