It is particularly true of wrestlers who cut their teeth in the ring during the 1970s and 1980s. Mick Foley, Terry Funk and Bret Hart are a few who come to mind, and even announcers like Jim Ross know how to spin interesting tales.

Those years driving from town to town, when pro wrestling was still a sport that thrived in “territories” nationwide, gave competitors plenty of fodder to have fun, tell stories and scratch out a living.

Add Steve Keirn to the mix.

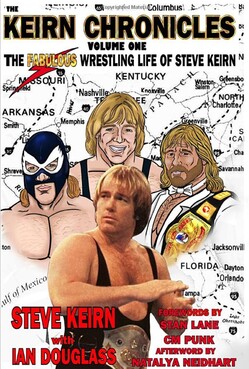

Keirn Chronicles Volume One: The Fabulous Wrestling Life of Steve Keirn (WOHW/Darkstream Press; paperback; $24.98; 419 pages), written with Ian Douglass, is an unvarnished look at his career. Keirn is an engaging storyteller, and he is alternately funny, blunt and at times quite harsh. But there is no doubt that Keirn, now 71, is a straight shooter about his life experiences and the pro wrestling business.

Looking behind the curtain and into the booking offices always makes for fascinating reading.

Fans of Eddie Graham’s Championship Wrestling From Florida promotion will remember Keirn as a young babyface. Later, Keirn would excel in tag team wrestling as one-half of The Fabulous Ones with Stan Lane during the 1980s.

Douglass is no stranger to wrestling, having collaborated on autobiographies for Buggsy McGraw, B. Brian Blair and Dan Severn. He also wrote Bahamian Rhapsody, a history of pro wrestling in the Bahamas from 1960 to 2020.

The reader hears Keirn’s voice throughout Keirn Chronicles, which is the mark of a good collaborator.

Keirn had a wrestling angle that was irresistible. His father was a prisoner of war during World War II for eight months, and then for nearly eight years in North Vietnam during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It was a perfect angle because heels like Bob Roop could criticize Col. Richard Keirn for “allowing” himself to be captured, or to question his courage.

Steve Keirn would take umbrage, a fight would ensue, and grudge matches would be held. As any wrestling promoter will tell you, the bottom line is making money.

Keirn’s father was amenable, so the angle worked. It is certainly not the most tasteless wrestling angle ever, but definitely one of the edgier ones.

While Keirn was growing up, Graham would take a role in his development, turning into a “father figure.” Keirn would do odd jobs, picking up wrestlers at Tampa International Airport, serving as a ring announcer and even serving as a referee.

But Keirn and Mike Graham were friends in high school and also had some success as tag team partners in Florida before business outside of the ring got in the way.

Keirn attended Robinson High School in Tampa, the closest high school to MacDill Air Force base. He would become a member of the school’s “Junior Mafia,” which included future wrestlers Mike Graham and Dick Slater. It becomes apparent after reading some of Keirn’s stories about Slater that he was as wild and unpredictable in real life as his wrestling character was. Slater, who died in October 2018, certainly earned his nicknames of “Dirty Dick” and “Mr. Unpredictable.”

“Slater’s got the best right hand I’ve ever seen,” fellow wrestler Ron Fuller once said. “Slater’s got the best punch I’ve ever seen.”

Another acquaintance of Slater was a young Terry Bollea, who would rise to fame as Hulk Hogan. Keirn writes that he tried to dissuade Hogan from wrestling, even when the teen would watch enthusiastically at Tampa’s steamy Sportatorium, a nondescript building where television tapings would occur. Keirn urged Hogan to stick to playing the bass guitar, but was ignored. The decision was a good one for the Hulkster.

Other wrestlers have written about Eddie Graham’s obsession with maintaining “kayfabe” — presenting the staged wrestling matches and interviews as if they were genuine — Keirn confirms that. Graham was a stickler for keeping the heels and babyfaces apart, even in public. For opponents to be seen together away from the ring was grounds for dismissal.

After doing the menial work for Graham, the promoter decided it was time to break Keirn into the business.

“I’m gonna break you into the business the real way,” Graham told him.

Keirn trained with Hiro Matsuda and received some sage advice from Jack Brisco — my favorite wrestler while growing up, by the way — to pay attention, watch and learn.

“You have to be like a sponge, because you’re a minnow in a sea of sharks,” Brisco told him. “And if you don’t like somebody, never let them know it. Be kind and humble.”

Wrestlers during the 1970s and '80s had to travel, usually by car. In Florida, that meant seven nights a week on the road, plus there were interviews to tape. Grueling stuff. In Georgia, Keirn would have a scary flight with fellow wrestler Ronnie Garvin piloting a small plane in southern Georgia. Years later he would have even scarier experiences with Graham piloting planes around Florida with wild abandon — and not always while sober, Keirn writes.

Competing at venues like the state mental hospital in Georgia could also be like insanity for a young wrestler.

Keirn paid his dues as a young wrestler, being a “jobber” in the early matches and traveling to Guatemala to wrestle as a masked heel. But he persevered and even was named rookie of the year by The Wrestling News in 1974.

As a promoter, Graham “was such a genius,” Keirn writes. Meticulous to a fault, Graham was detail-oriented and adept at “creating great wrestling moments,” including the buildup to the end of the match.

Keirn tells a hilarious story about Dusty Rhodes getting a traffic ticket after bragging that “there’s not a highway patrolman, not a sheriff, and not a police officer in the state of Florida who would give the American Dream a ticket.”

Except this officer, who did not watch professional wrestling. I won’t give away the punchline, but Rhodes’ retort was priceless.

Keirn does write about wrestling territories other than Florida — Memphis and the AWA areas, for example — but I was fascinated with the Sunshine State stories because I grew up watching many of the wrestlers and wanted to know more of the inside stuff. I was not disappointed.

At one point, Keirn said he borrowed $50,000 from his future father-in-law to buy 2.5% percent of Championship Wrestling from Florida. But when he received cash in bags after shows, he became suspicious and confronted Eddie Graham. Keirn got his initial investment back and got out of the ownership business in Florida.

Eddie Graham eventually committed suicide in early 1985. Keirn is harsh in his assessment.

“People need to come to grips with the fact that your idols and mentors will always let you down, and that’s a scenario that played out in my life,” Keirn writes.

To be fair, neither Eddie Graham, nor Mike Graham, who would also commit suicide in 2012, are unable to rebut what Keirn has written. I wrote the Mike Graham story for The Tampa Tribune in October 2012, and that was a tough one.

But I did not do business with them or were as closely aligned (I did take calls at the Tribune’s sports desk when Mike Graham called in boat racing results), so Keirn’s assessment is obviously from personal experience and perception.

Keirn also writes about wrestling in Georgia for Jim Barnett, the Mid-Atlantic territory for the Crockett family, and even throws in stories about a stint in Japan.

Keirn would put the hold on opponents, and also execute the move on audience members at wrestling venues and people who would challenge him in bars. Even a doubting television host was not immune. The hold helped his credibility and allowed him to rise from the bottom of the wrestling card toward the top.

Keirn can be blunt. Evaluating the Fabulous Freebirds, he notes that Buddy Roberts and Terry Gordy were great workers but that Michael Hayes “was more interested in moonwalking rather than having a technically sound wrestling match.”

Roberts, Keirn said, never washed his tights.

Some wrestlers in Memphis “seemed to be locking up with all the aggression of two feeble old ladies.”

Harley Race “could put the fear of God in you” because he protected the wrestling business “at all costs.”

Nick Bockwinkel “was all show to me.”

My bias here is about Florida wrestling, and I eagerly read every word about the promotion, but Keirn’s greatest success came when he teamed with Stan Lane to form “The Fabulous Ones” from 1982 to 1987. Keirn goes into great detail about his partnership with Lane and their battles against the Moondogs and the Road Warriors.

The Fabulous Ones wore suspenders, bowties, top hats and jackets to the ring. It was an update to the Fargo Brothers gimmick that flourished in the Tennessee territory years before, and it worked for the MTV generation.

They would strut to the ring with songs like “Everybody Wants You,” by Billy Squier, and they cut a silly video that mimicked ZZ Top’s popular video at the time, “Sharp Dressed Man.” With their Nashville connections, Keirn and Lane got to escort Kenny Rogers to the stage during a concert. They even met Mike Love of the Beach Boys at the airport in Memphis.

The pair became wildly popular and profited from the sale of merchandise, a concept that was still in its infancy in the 1980s. They even started a wrestling school, but that venture did not pan out. However, the most notable pupil was future wrestler Tracy Smothers.

He once turned off Jerry Brisco’s air supply when they were scuba diving in the Gulf of Mexico. Keirn enlisted an off-duty police officer in Daytona Beach to “bust” Mike Graham at a hotel room and stuffed a live armadillo into Prince Tonga’s wrestling bag.

The best prank Keirn pulled was on Curt Hennig at Memphis International Airport. Keirn got a police officer to serve an arrest warrant on Hennig as he exited a plane, and the startled and confused wrestler fell for the ruse hook, line and sinker.

“I loved to get guys arrested,” Keirn writes. “Because of the great relationships I formed with cops, I was able to regularly rib guys by having them arrested during my career.

“After all, who is going to argue with a cop?”

While wrestling may be scripted, the injuries were real. When he broke his ankle and could not wrestle, Keirn had to borrow money from his parents to stay afloat financially.

“One injury had taken me from being on the top of the world to the depths of unemployment,” Keirn writes. “All I do was sit around while waiting for everything to heal up.”

Like many wrestlers, Keirn has had some close calls. He nearly died after he was cut in the temple with a blade from another wrestler while “getting color.”

The Keirn Chronicles is another wrestling book worth putting on the shelf. A new generation of fans may see the WWE’s slick production and angles, but the wrestling business Keirn saw when he began was still raw, unpredictable and very Darwinist.

“It was simultaneously exciting, and more than a little bit scary, because anything could happen in this business,” Keirn writes.

His wrestling autobiography helps fans understand the life of a truly fabulous one.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed