It’s the perfect lead-in to Jon Pessah’s thorough, crisply written history of the last two decades of baseball. “The Game” (Little, Brown and Company; hardback; $30; 648 pages) gives the reader a “you are there” look at the power, politics — and yes, money — through the eyes of three major characters.

Pessah, a founding editor of ESPN the Magazine, focuses on three main characters — baseball commissioner Bud Selig, MLB Players Association chief Don Fehr and New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. Armed with five years of research and interviews with more than 150 sources, Pessah writes in the present tense and takes the reader through labor squabbles, boardroom politics, revenue sharing, luxury taxes, salary caps, contraction, Congressional hearings, steroids and other performance enhancing drugs (PEDs).

All three men have their strengths and weaknesses, and Pessah captures them perfectly. Selig, who has a genuine love of baseball, nevertheless is a cagey back-channel arm-twister who rarely asks for a vote unless he knows the result will be in his favor. He owns the small market Milwaukee Brewers and becomes acting commissioner after Fay Vincent was ousted in what amounted to an owners’ coup.

Bud Selig led baseball from 1992 to january 2015.

Bud Selig led baseball from 1992 to january 2015. Baseball fans will remember that Selig was baseball’s czar during a crippling strike in 1994 that also canceled the World Series, and made the decision to end the 2002 All-Star Game in Milwaukee in a tie when both teams had run out of players. They also will point to Selig seemingly turning a blind eye to steroid use in the mid-1990s, while baseball rebounded from the strike with a home run race for the ages between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998.

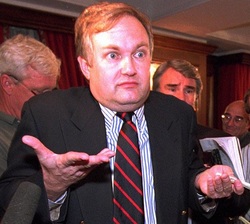

Union boss Don Fehr was perplexed and frustrated when the 1994 strike crippled baseball.

Union boss Don Fehr was perplexed and frustrated when the 1994 strike crippled baseball. Pessah is more lenient toward Fehr, who retired as the union chief in 2009, but does not give him a free pass. He documents how Fehr’s stubborn resistance to drug testing made eliminating PED use a much tougher road. And he notes the hostility between Fehr and Selig; Fehr does little to hide his contempt, and Selig has equal “warmth” for the union boss.

“Nothing infuriates baseball’s owners more than the media calling Fehr the game’s most powerful man,” Pessah writes. “Selig believes all Fehr really cares about is getting big money for his players.

“And that’s why he has to be stopped, if not driven from the game completely.”

It never happened. Fehr left on his own terms.

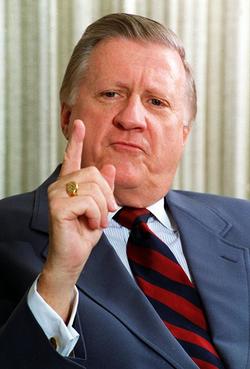

Among baseball's owners, George Steinbrenner was the straw that stirred the drink.

Among baseball's owners, George Steinbrenner was the straw that stirred the drink. Pessah writes about Steinbrenner’s rocky relationships with his manager, Joe Torre; his general manager, Brian Cashman; and his love-hate relationship with Selig. Steinbrenner and Selig consider each other friends, but that does not stop them from butting heads — particularly when the issue is costing Steinbrenner money. The luxury tax is a key example.

Plus, the more deals Steinbrenner pulls off — his television contracts pour millions into his pocket and enable him to continue paying huge salaries and target lucrative free agents — the more Selig tries to reach into the Boss’ wallet to help the smaller market teams.

But it was Steinbrenner’s passion — and his money — that brought the Yankees back to relevance in the mid-1990s, and New York won five American League pennants and four World Series titles from 1996 to 2001.

There are other characters within “The Game” who receive good play — for example, George W. Bush, at the time the managing partner of the Texas Rangers, who aspired to be the next commissioner of baseball after Vincent was ousted. Selig effectively blocked that goal, and Bush went on to political success as governor of Texas and, later, president of the United States.

Sonia Sotomayer was a federal district judge in 1995 when she ruled in favor of the union, effectively ending the baseball strike. Sotomayer is now a Supreme Court justice.

“The Game” does not really focus on the game of baseball — nor does it pretend to. Certainly there were great on-field events. Some of them, unfortunately, have since been tainted by the specter of PEDs. Selig and Fehr share equally, along with the media, in not recognizing the damage steroids was causing. It’s easy to turn a blind eye when baseballs are flying out of the park and stadiums are filling to capacity with fans eager to see home runs.

But while the on-field stuff is important, it is not the focus of Pessah’s work. Over the past two decades, a bigger and more contentious game was being played away from the diamond.

Will there be another work stoppage? With baseball producing billions in revenues and player salaries at an all-time high, it seems unlikely.

But, Pessah writes, when Fehr and Selig were going head to head, there was always that chance.

Fehr “still knows it is dangerous for the players to let down their guard, as long as the man sitting to his left (Selig) remains the Commissioner of baseball.”

Both Selig and Fehr are out of the picture now and Steinbrenner died in 2010, but the trio provided a fascinating chapter in baseball labor relations.

Pessah documents that rocky road with a timely, concise and entertaining prose. The book is not for everyone. If you’re geared solely toward statistics, fantasy baseball and whether the Mets’ pitching staff can lead New York to the World Series, “The Game” might not contain the minutiae you’re seeking.

But if you want a level-headed look at what took place over the past two decades—and with labor negotiations looming in 2016 — “The Game” is a must read.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed