For the past 15 years, Fitts has produced some of the finest books about Japanese baseball, and his fifth work combines his trademarks — anecdotal storytelling, backed by careful and exhaustive research.

Books about Japanese baseball might seem to fall into a niche group, but if you enjoy baseball and history — and by extrapolation, baseball history — then Fitts’ latest effort will be a satisfying read.

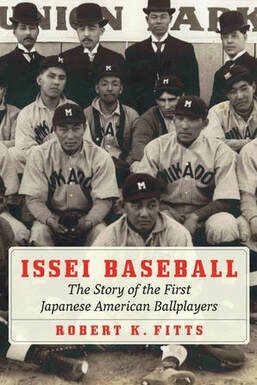

Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese Baseball Players (University of Nebraska Press; hardback; $29.95; 309 pages) was inspired by an eBay purchase. In 2003, Fitts, an avid baseball card collector, bought a card that depicted a team of Asian players wearing “J.B.B. Association” jerseys. Intrigued, Fitts learned the Japanese Base Ball Association squad barnstormed across the United States in 1911.

Ten years later, while researching Mashi, his 2015 book about Masanori Murakami, the first Japanese major leaguer, Fitts learned more about the JBBA. He was hooked.

“Before I had even started writing Mashi, I had targeted the topic of my next book,” Fitts writes.

Issei Baseball is the culmination of four years of research and continues Fitts’ deep dive into Japanese baseball. He started with an oral history, Remembering Japanese Baseball, in 2005, followed three years later by a biography of Wally Yonamine, the first Asian-American to play pro football and the first American to play professional baseball in Japan.

Fitts’ best-known work, Banzai Babe Ruth, breathed new life into the 1934 goodwill tour of major leaguers to Japan, led by Ruth. The 2012 book earned Fitts a Seymour Medal from the Society of American Baseball Research.

In Issei Baseball, Fitts focuses on five men who would play a large role in shaping Japanese baseball in the United States before World War I — Harry Saisho, Ken Kitsuse, Tom Uyeda, Tozan Masko and Kiichi Suzuki. Japan had been introduced to baseball in 1871, and by the turn of the century, these men would come to the United States to start new lives. They found athletics as an outlet to showcase their and would later play big roles in barnstorming tours in 1906 and 1911.

They had a receptive audience in the Great Plains because major league baseball did not exist west of St. Louis. Guy Green, “a savvy businessman,” recruited Native Americans to form the Nebraska Indians, who played 103 games during an 1898 barnstorming tour. Green decided to do the same with Japanese players in 1906. He created a promotional card to tout players “direct from the schools and universities of Japan.”

They did.

Still, the advertised “Japanese team” would play for 25 weeks and travel 2,500 miles through eight states and two territories. There is no record, Fitts writes, that the team used an all-Japanese starting lineup for the rest of the tour after nearly losing to a high school squad in Frankfort, Kansas.

“The Japanese ball team was not what the Jap’s advertising manager cracked it up to be,” one reporter would comment later during the tour.

The 1911 team included many of the same players, with Saisho acting as manager and promoter. This time, most newspapers praised the Japanese players for mastering the game and showing good sportsmanship.

Fitts was hindered at times by the lack of newspaper coverage of the Japanese tour, but he kept digging.

The team played 128 games in 143 days, playing in front of tens of thousands of fans across seven states. Results from 87 of the games can be documented, and the JBBA squad had a 25-60-2 record, Fitts writes. The team earned $4,556.88 in gate receipts, but when the tour ended in St. Louis the balance had shrunk to $2.27 after expenses. The team had to borrow money to get back to Los Angeles.

What is particularly stunning about this Issei Baseball is how American newspapers were blatantly racist in their portrayal of Japanese players.

Fitts writes that Japanese people in the United States were banned from restaurants, barbershops and housing in certain neighborhoods. Finding jobs was also difficult.

In southern Colorado, a mining area “not known for its tolerance” of the Japanese, immigrants were treated harshly. The hatred grew when Japanese and Mexican workers were brought in as strike-breakers by mining companies. In 1911, for example, local men and boys attacked the home of George Ikeda, smashing windows and forcing the merchant and his wife to hide in their basement.

The Japanese were called the “yellow peril” by newspapers. One newspaper produced this gem of a headline: “Twirlers are Japanesy, but Not Easy to Defeat.” The San Francisco Chronicle warned in large headline type about “The Japanese Invasion, the Problem of the Hour for the United States.” Shortening their nationality to “Japs” was the norm. “Little yellow men” and “tricky Orientals,” were common descriptions.

Congressman Richmond Pearson Hobson, from Alabama, viewed Japan as a military threat and had little use for anyone of color. “The whole trend of events is … toward a content by the yellow race, aided by the other colored races, a struggle to wrest from the white man his present superiority,” Fitts quotes Hobson from a 1907 New York Times article.

Taziko “Frank” Takasugi would characterize Hobson as a “double bonehead,” Fitts writes.

At Our Game, a guest column by @robfitts, author of a fine new book. The First Japanese Professional Game Took Place in …. Kansas? https://t.co/8BuWalBPUk

— John Thorn (@thorn_john) April 13, 2020

The Japanese players’ behavior nevertheless earned them respect in the Midwest, “undercutting negative stereotypes,” Fitts writes.

The team was not a financial success, but it did lead to other Japanese-American squads.

Fitts’ research was based on sources in Japan, California and the barnstorming towns in the Midwest. He draws from archives, books and websites. His bibliography runs 10 pages and there are endnotes for every chapter. Schedules and game results, where available, are included in an appendix. A second appendix lists known Issei baseball teams from 1904 to1910, and a final appendix lists partial rosters of selected Issei teams.

Fitts’ research uncovers wonderful nuggets of information. Saisho, for example, was the eldest son of a samurai war hero and part of a family of warriors that can be traced to the 11th century. One of his possible relatives, Atsushi Saisho, was the grandfather of Yoko Ono.

As a postscript, Fitts follows the former players as they aged. Some of them suffered the indignity of confinement in Japanese internment camps during World War II. They were taken from their homes, limited to two suitcases apiece, and moved inland to inhospitable places.

The internment had an ironic effect, bringing “a respite from a lifetime of backbreaking work and struggle.” Athletics played a big part, as camp members built baseball fields and formed leagues to pass the time.

For the Japanese players of the early 1900s, the shared love of the game acted “as a bridge between people from different sides of the globe,” Fitts writes.

And in Issei Baseball, Fitts once again has unearthed valuable insights, adding to our knowledge and understanding of baseball history.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed