That is an unfair assessment, particularly for a member of the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Berra played 19 years in the major leagues and was a three-time American League MVP (he finished second twice). He was an essential piece of the New York Yankees machine that won five consecutive World Series titles from 1949 through 1953.

A workhorse behind the plate, Berra caught no fewer than 109 games in a season from 1949 through 1957.

Berra bridged the eras between the Yankees of Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle, but he was a star in his own right and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1972.

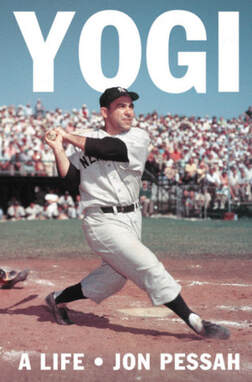

That is what shines through in Pessah’s Yogi: A Life Behind the Mask (Little, Brown and Company; hardback; $30; 567 pages). Pessah spent 4½ years doing research and conducted more than 100 interviews.

“It felt like he was sitting on my couch the last year I was writing the book,” Pessah, who writes for The New York Times and was a founding member of ESPN the Magazine, told Newsday earlier this year.

Berra, who died in 2015 at the age of 90, was baseball’s Everyman. He did not look like a major leaguer, standing 5 feet, 7 inches tall and weighing 185 pounds in his prime. His physical appearance and Italian heritage made him an easy target throughout his career.

But Berra’s first manager counseled him to ignore the slurs, reasoning correctly that if the young player responded, the bench jockeying would only get worse.

So, while Berra let the taunts slide, he never forgets them, Pessah writes.

Berra’s reading material may have been confined to comic books, but he was a savvy businessman and a tough bargainer at contract time, Pessah writes.

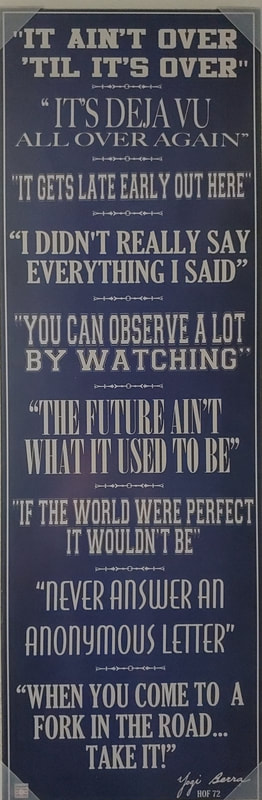

I have a sign on the wall in my office that has phrases attributed to Berra — “It ain’t over ’til it’s over,” “You can observe a lot by watching,” “It gets late early out there,” “It’s déjà vu all over again,” and “When you come to a fork in the road, take it.”

“Every time Yogi hiccupped, he was answered by gales of laughter,” Bill Veeck once wrote. “Boy, you said to yourself, nobody can hiccup as funny as that Yogi.”

That image was manufactured by the writers who followed the Yankees, who were trying to turn a quiet, almost dull personality into a savant of baseball witticisms. Pessah does a nice job of sifting fact from fiction.

Berra was a serious, quiet man who enjoyed playing baseball. He did not have to be flamboyant or colorful, and he shunned the spotlight. Berra was, however, a solid hitter who held the career record for home runs by a catcher (now owned by Mike Piazza.). Berra was a tough out and a dangerous clutch hitter who would swing at any pitch.

In George Vecsey’s 1966 book, Baseball’s Most Valuable Players, Detroit pitcher Hal Newhouser was told not to worry — Berra was a bad-ball hitter, and he should have no problem getting the catcher out.

“Yeah,” Newhouser said. “But I defy anyone to throw him a good pitch.”

When I was a kid growing up in Brooklyn, New York, during the mid-1960s, Berra remained popular even though he was retired. The catcher on my Catholic school’s baseball team was naturally nicknamed “Yogi,” for example, and all of us enjoyed Yoo-hoo, a chocolate drink endorsed by Berra.

Berra was gold for advertisers, too, from Yoo-hoo to Aflac. Berra showed his business acumen by skipping a salary for representing Yoo-hoo, electing instead to be paid in company stock. It made him rich, Pessah writes.

“When Yogi bought stock, the market went up. When he sold, it went down,” Yankees pitcher-turned-author Jim Bouton wrote in 1973. “Yogi got into the bowling business (with teammate Phil Rizzuto) just before the boom and got out just before the crash.”

Berra, like many sons of immigrants, had to convince his father that baseball was not frivolous, and that was not an easy task. Even though his older brothers picked up the slack and brought home extra money, Pietro Berra remained unconvinced that baseball was a way to make a living.

Pessah chronicles Berra’s youth, his career in the Navy and his harrowing landing at Utah Beach at Normandy on D-Day. Later in 1944, Berra is wounded in his left hand while manning a machine gun in Marseilles, which would earn him a Purple Heart.

Compared to Berra’s military service, playing baseball was a cakewalk.

For all the teasing and indignities he suffered early in his professional baseball career, Berra remained resilient — and stuck to his guns.

When a clubhouse man for the Newark Bears hands Berra a well-worn uniform that lacked a number on the back and the city name on the front, the young catcher “wraps the uniform into a ball, strides angrily over to the clubhouse man” and tosses it at the worker.

“Hey, give me a damn new uniform,” Berra says, “I’m not trying out. I play for this club!”

Berra got the new uniform.

Pessah tracks Berra’s career with the Yankees, where he played in 12 World Series and won 10 titles. Berra was the glue that kept the team together. For example, in August 1951 he caught all but one game and both games in five out of six doubleheaders, Pessah writes. Five days after the birth of his son, Tim, Berra is poised to help Allie Reynolds make history when he settles under a foul pop. Reynolds is one out away from his second no-hitter that would also clinch the 1951 pennant, but Berra drops the ball.

Considering that the hitter was Ted Williams, giving the game’s best hitter a second chance seemed like an invitation to disaster. But Williams popped up again and Berra caught the ball, to his everlasting relief.

Pessah does a good job in writing about chunks of Berra’s career, but the chapter called “A Second Chance: 1965-1972” is a curious one. Instead of recapping what took place when Berra joined the New York Mets in 1965 — including a stunning World Series win in 1969 — Pessah jumps to 1972, when manager Gil Hodges died, and Berra was named to replace him.

I’m not certain that anything of note took place in Berra’s world from 1965 to 1971 that would have added to the book, but it just seemed a bit incongruous, given that every other era of his life was covered so thoroughly.

Berra led the Mets to the World Series and took the defending champion Oakland A’s to seven games before losing. However, Berra’s fortunes would shift back to pinstripes after he was fired by the Mets and hired by the Yankees as a coach.

Berra would be named the Yankees’ manager in 1984, but when owner George Steinbrenner fired him 16 games into the 1986 season, the wounded legend boycotted his team for 13 years. Until Steinbrenner apologized — on Berra’s turf, face to face — the former star stayed away from Yankee Stadium. Interestingly, Berra and Steinbrenner became good friends after the boycott ended.

Pessah delves deep into the family relationships Berra had with his parents and siblings, his longtime love affair with his wife, Carmen, and the turbulent times caused by the drug use of his son, Dale. Through it all, Berra remained stoic and enjoyed his later years, particularly the opening of the Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center.

Two months after his death, Berra was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama.

"We know this for sure: If you can't imitate him, don't try to copy him," Obama said in a nod to one of Berra’s famous sayings.

There is no doubt that Berra lived a long, full life. Pessah presents that life in a warm narrative that will resonate with baseball fans.

The book is thick, but it is a fast read. And the best part? It ain’t over ’til it’s over.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed