But while Robinson used a “relentless fighting spirit” to earn his place in the majors, author Gaylon H. White writes that Artie Wilson used “singles and smiles” to help desegregate the minor leagues.

That’s the title of White’s warm, sentimental biography of Wilson, a shortstop who was known as “Artful Artie” during his years in the Negro Leagues and the Pacific Coast League.

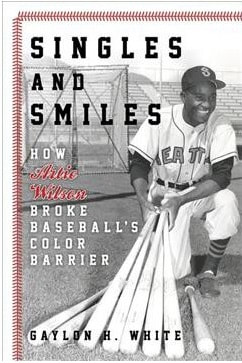

Singles and Smiles: How Artie Wilson Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier (Rowman & Littlefield; hardback; $35; 233 pages) follows the career of Wilson, a gifted hitter and fielder who never got the chance to showcase his talents in the majors. Brought up to the New York Giants in 1951, Wilson went only 4-for-22 (a .182 average) before being shipped back to the minors to make room for a young outfielder named Willie Mays.

In fact, White writes, Wilson lobbied the Giants to bring Mays to the majors, even at his own expense. Wilson “focused on the big picture, not the big leagues,” White writes.

The title of the book is mostly appropriate: Of his 1,609 career hits in the minors, Wilson collected 1,365 singles and batted.312, including a .402 mark in 1948. One early criticism leveled against the book was that its title implied Wilson was the pioneer who broke the modern color line. Perhaps inserting the phrase “Helped Break” after his name in the title would have cleared up any confusion. It’s really a minor point: Baseball historians — and even casual fans — know that Robinson was the man who took the first steps toward racial equality in the game.

What’s accurate beyond question, however, was Wilson’s ability to smile. He had a joyous love for baseball and was eager to play it, whether it was in a Birmingham industrial league in his native Alabama, the Negro Leagues, the Pacific Coast League or the majors. Long before Ernie Banks, Wilson was the player who was happiest on a baseball diamond.

Wilson was the second black in the PCL and the first to play for the Oakland Oaks and the Seattle Rainiers. The PCL was one of the first leagues to have all its franchises integrated within a decade of Robinson’s shattering of the color line.

White excels at examining the careers of players who, while not famous today, were notable during their heyday. His last book, a collaboration with former major-leaguer Ransom Jackson, was an engaging look at the player brought to the Brooklyn Dodgers to replace Robinson. Even though he could not wrest the starting job from Robinson in 1956, “Handsome Ransom” overcame the pressure and carved out a respectable career. In Singles and Smiles, White follows the same formula to show how Wilson did not allow pressure or disappointment cloud his sunny outlook on the game and in life.

White, who interviewed Wilson before the player’s death in 2010 at age 90, coaxed several opinions out of the former infielder. Robinson, Wilson said, was the only man who could have endured the abuse and vitriol hurled at him during his rookie season with the Dodgers in 1947.

“He had the tools, the know-how,” said Wilson, who was one of several black stars passed over in favor of Robinson. “I’m not saying these other guys couldn’t do it now. I just don’t think they would’ve gone through with it like Jackie.

“That is why I like Branch Rickey. He picked the right man.”

Wilson also thought that Jim “Junior” Gilliam should have been the first black manager in major league baseball instead of Frank Robinson.

“I would’ve taken Gilliam over any of them,” he tells White.

Wilson was such a consistent hitter that other managers employed shifts to prevent him from slapping singles to all fields. Wilson also had a penchant for fouling off pitch after pitch, frustrating pitchers until they threw him what he wanted to hit.

White expands one of the more entertaining anecdotes about Wilson’s time in the majors when he made an appearance in the Giants’ home opener. The story originally appeared in an essay by John Lardner and featured a battle of wits between Leo Durocher and Charlie Dressen in an April 20, 1951, game at the Polo Grounds. Durocher sent Wilson to pinch hit for the Giants in the seventh inning and the Giants trailing 7-3.

Dressen brought Carl Furillo in from right field and stationed him at second base, putting three infielders on the left side of the infield. Dressen was daring the Wilson to pull the ball; instead, he hit a one-hopper to the mound and was retired when Don Newcombe threw him out.

Dressen had managed Wilson at Oakland, so he knew a way to foil his former player. Durocher’s reaction, as expected, cannot be printed.

After an eye injury ended his career in 1957, Wilson found success for nearly a half century as an automobile salesman in Oregon. A flashy dresser who was called “Dude” by his teammates, and with a love for children, Wilson made a smooth transition from the game to business. He retired in 2005, but not before making a new group of friends. Wilson never seemed to try and pressure potential buyers, White writes. He was more content to talk baseball with customers. Invariably, that led to a sale.

White’s research included delving deep into newspaper archives, but he also did interviews with more than 30 former players, including Mays. A former sportswriter and businessman, White writes with an easy conversational style that tells a compelling story. His interest in West Coast baseball and integration shows in his approach to the Artie Wilson story.

Wilson was more than a footnote in baseball history. His legacy, while not widely known, still resonates today. Wilson’s sacrifices — he experienced racism firsthand and never flinched, doing it with a smile and a friendliness that did not mask his competitive spirit — helped make integration a reality in leagues like the PCL. In Singles and Smiles, White adds a needed chapter to baseball history.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed