A large checklist that includes a base set supplemented by a 100-card rookie set, is enough to whet any NFL’s fan’s appetite.

The Score set does have 300 base cards that feature veteran players and all-time greats.

I bought a blaster box, and even though I bemoan the rise in prices for cards, I at least felt better after buying the 2023 Score blaster at $24.99. That is because there are 132 cards per box — six packs, with 22 cards to a box.

As a blaster exclusive, Panini is also promising one numbered parallel per box.

A note about the set: For some reason there is no card No. 331, but two players share No. 301 — Bryce Young and Camerun Peoples.

The blaster also included four gold parallels, and the numbered card was a Lava parallel of Deuce Vaughn, numbered to 565.

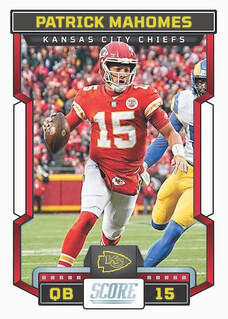

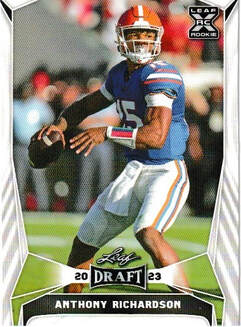

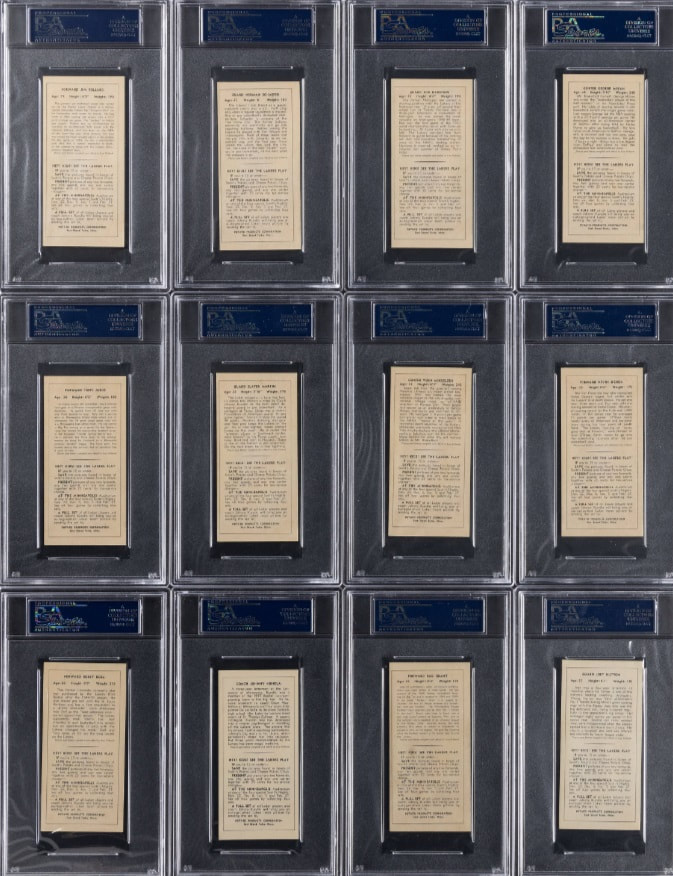

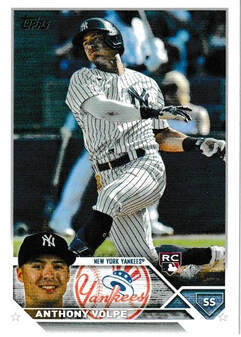

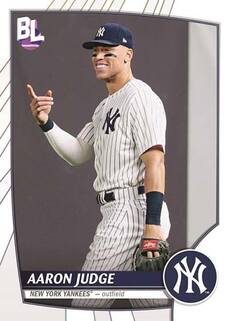

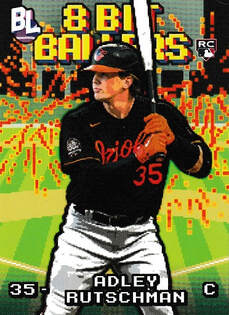

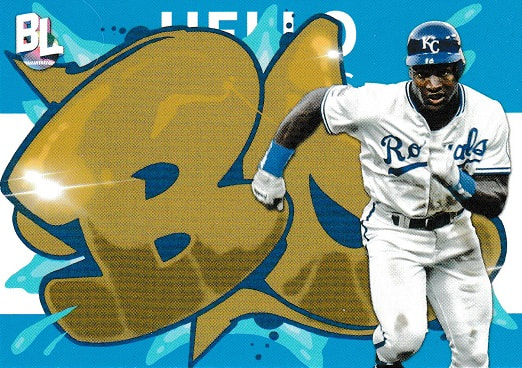

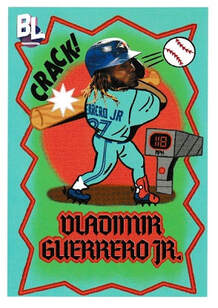

The card front design is vertical, which I love. The player’s name is tastefully presented in yellowish-gold block letters set against a black nameplate.

The photograph that dominates the card front is an action shot that is framed by a thick, angling black line that gives it a die-cut look.

The team logo is beneath the photograph, with the Score logo stamped in silver foil below that.

Flanking the Score logo is the player’s position and his uniform number.

The card backs are also vertical, with the team logo dominated the upper part of the card.

The player’s name is beneath the logo and an eight-line paragraph detailing highlights and fun facts. The type is ragged center, which is kind of disconcerting, but it is not a distraction — except to me, of course, who prefers ragged right type.

Huddle Up is a 15-card subset that sports a horizontal design and features teams huddling up for a play. I pulled five cards, including the Bears, Broncos, Dolphins, Steelers and Titans. The back of the card presents information of each of that team’s starting quarterbacks, who command the call-playing in the huddle.

Celebration, as the name implies, shows players in various stages of celebration after a key play or a clinched victory. There are 25 cards in the subset, and I pulled five of them. The players reveling in my blaster box were Ezekiel Elliott, Danielle Hunter, Aidan Hutchinson, JuJu Smith-Schuster and George Kittle.

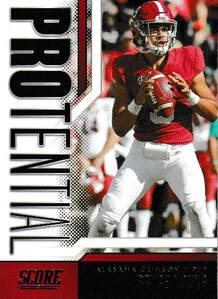

The cleverly named Protential insert set includes 25 cards. I managed to pull six of these cards, including Bryce Young, Max Duggan, Michael Mayer, Jahmyr Gibbs and Bijan Robinson.

Sack Attack features defensive stars getting to the quarterback. I pulled four of the 15 cards in the subset — Hutchinson, Micah Parsons, Nick Bosa and Von Miller.

The 10-card 2003 Throwback Rookie Set, uses elements similar to that year’s design from score. I pulled a pair of cards – Young and Will Anderson.

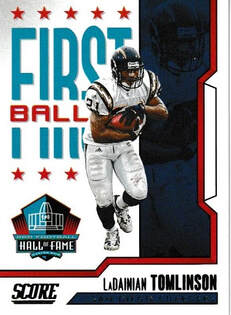

First Ballot features 10 players who were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in their first season of eligibility. The card I pulled was of LaDainian Tomlinson.

With NFL training camps already in full swing -- the Hall of Fame Game was already played on Thursday -- this set is a good way to ease back into football card collecting this year.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed